Nowadays, the majority of biopsies performed in the hospital are carried out in the Radiology department. Most of these are performed with local anaesthesia on its own or with a combination of local anaesthetic and light sedation using midazolam. Only a very small proportion of image-guided biopsies require the use of deeper sedation with a combination of midazolam and fentanyl; a general anaesthetic is almost never necessary (usually only for very painful lesions, such as an osteoid osteoma of bone).

Biopsies are performed through tiny (less than 5 mm) incisions in most cases; sutures are not required. If the patient is expected to require sedation he or she is admitted as a day case, and discharged once the sedation has worn off. When the biopsy is performed under local anaesthetic only, the patient can go home immediately after the procedure.

There are two forms of biopsy that we commonly perform: fine needle aspiration (FNA) and core biopsy.

FNA involves the use of a small calibre (23 G or 25 G) needle to aspirate some material from a lesion; the aspirate is then smeared on some histology slides or is sent in fluid for cytology. FNA is performed for most thyroid lesions, for some breast lesions and for some lymph node biopsies.

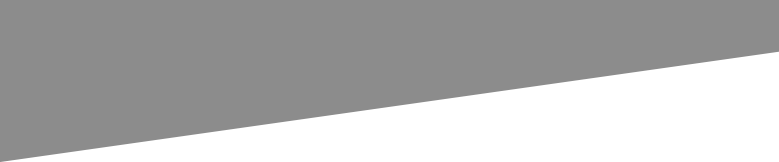

For most of the remainder of our biopsies, we use a spring-loaded ‘Trucut’ biopsy needle to obtain a core of tissue. These needles are available in a variety of lengths and sizes – the most commonly used is an 18 G needle, however 20 G (which is smaller than 18 G) is typically used for lung biopsies, and 16 G may be used for large superficial lesions.

This is the most commonly used biopsy gun in our department. It is often used in tandem with a co-axial needle (top image) which can be advanced into the organ/lesion first, before advancing the biopsy needle. There are two components to the biopsy needle. When the gun is ‘fired’, an inner component springs forward first – this has a shelf that allows tissue into it (bottom left image). The outer component of the needle automatically advances over the inner needle (bottom right), trapping that tissue sample in the shelf.

Wherever possible, we prefer to perform needle biopsies under ultrasound guidance, as it is fast, inexpensive, does not use ionizing radiation and provides us with real-time imaging of the position of the biopsy needle relative to the target. However, in many cases ultrasound-guided biopsy is not feasible and CT is required. This is routine in lung and bone biopsies (as ultrasound cannot see into either of these structures), but is also required when accessing some deep liver, renal or retroperitoneal lesions.

Until recently, MRI has not been used for biopsies because of the obvious problems associated with bringing needles into the magnet, however MR-compatible biopsy equipment is now available. Currently, we reserve MR-guided biopsy slots for the biopsy of a small number of selected breast cancers (when they are only visible on breast MRI).

Biopsy of specific organs

Lung Biopsy

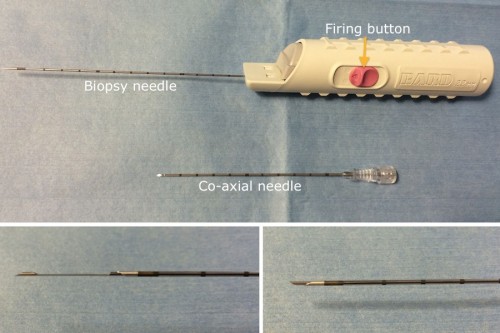

This is performed under CT guidance, and is used to diagnose primary lung tumours as well as metastatic disease. It is a relatively painless procedure, and can be performed without any sedation. There is a significant (15-20%) risk of pneumothorax following a lung biopsy, therefore patients are monitored closely for a few hours afterwards, and have routine chest radiographs one and three hours post-procedure. Most of these pneumothoraces are small and asymptomatic, however a small percentage will require a chest drain to be inserted.

CT guided lung biopsy. This 73 year old smoker (note the hyperinflated lungs) has a large irregularly-shaped mass in the left upper lobe, suspicious for a primary lung tumour. An image from her CT-guided lung biopsy is shown on the right, displaying the biopsy needle at the edge of the mass.

Liver biopsy

The main indications for performing a liver biopsy are for the diagnosis of chronic liver disease, to characterize focal liver lesions (usually metastases), and for suspected rejection of transplanted livers.

While we usually know that a liver lesion is a metastasis before biopsying it, tissue is generally required in order to confirm that the metastasis is from a known primary (especially if the primary lesion is more difficult to biopsy, for example pancreatic adenocarcinoma), or to tell us where to look for the primary tumour if we have not identified one on imaging to date, or to assess the characteristics of the metastasis (for example, hormone receptor status in breast cancer). We usually don’t need to biopsy hepatocellular carcinomas, because we can usually make a specific diagnosis with contrast-enhanced CT or MRI; this is fortunate, because HCC has a tendency to seed along the path of needle biopsies and is therefore prone to recurrence in the abdominal wall or subcutaneous fat.

The most serious potential complication of liver biopsy is haemorrhage. This is usually not a significant problem, but in rare cases may be sufficiently torrential to require intervention – it can usually be managed in Interventional Radiology with embolization.

Image from an ultrasound-guided liver biopsy, showing the biopsy needle taking a core from the periphery of the liver.

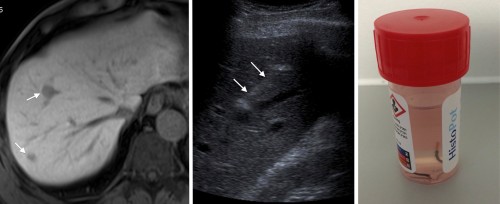

This patient was diagnosed with ocular melanoma. MRI liver, left, performed because of the suspicion of metastatic disease on staging CT, shows two probable metastases (arrows). A targeted ultrasound-guided liver biopsy was performed (middle image, needle indicated by arrows). The specimens this yielded are in the pot of formaldehyde on the right. Note how the majority of the tissue in both samples is black – this is due to the presence of melanin.

Kidney biopsy

This is usually performed in the setting of acute or chronic renal failure, in which case several non-targeted samples of cortex are obtained from one kidney. Occasionally we are asked to biopsy focal renal masses where the patient’s imaging has not allowed a specific diagnosis to be made.

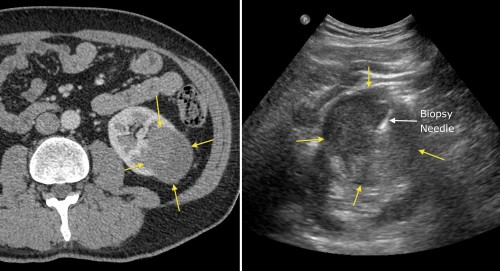

Ultrasound guided biopsy of a left renal mass identified on CT (yellow arrows), which confirmed renal cell carcinoma.

Thyroid FNA

Fine needle aspiration is usually sufficient to allow an accurate diagnosis of thyroid nodules. Ultrasound can identify features of thyroid nodules that make them more likely to be malignant than benign, and helps us to decide which patients (and which nodules, as many patients have more than one) require FNA.

Breast biopsy

This is usually performed after mammography and ultrasound have identified a suspicious lesion. FNA or trucut needle biopsy may be performed, depending on the size and nature of the lesion. Most breast biopsies are performed under ultrasound guidance, however some lesions that are identified on mammography are not visible on ultrasound, in which case a procedure called ‘stereotactic’ biopsy is performed. This involves using radiographic imaging from two different angles to help guide a needle into a lesion. Occasionally, MRI-guided breast biopsy is performed (see above).

Lymph node biopsy

We commonly perform ultrasound-guided biopsy of cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes, when there is a suspicion of metastatic disease or lymphoma. Deeper lymph nodes (mediastinal, retroperitoneal and pelvic) usually require CT guidance for biopsy.

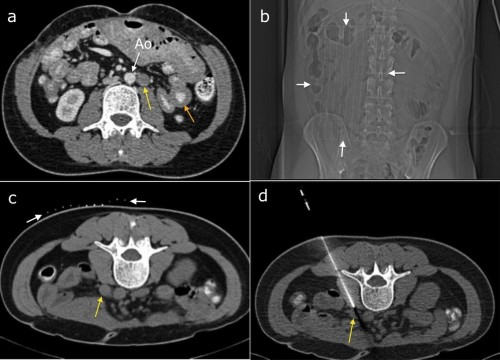

This patient’s CT, (a), showed small bowel wall thickening (orange arrow) and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (yellow arrow, beside the abdominal aorta, Ao). The appearances were concerning for lymphoma and CT-guided biopsy was requested. To localize the correct skin site for needle insertion, a paper grid with radio-opaque lines drawn on it is taped to the skin (scout image (b), arrows). A scan through this region then allows the Radiologist to pick an appropriate slice (c) on which the lymph node is best visualized (yellow arrow). The grid (white arrows) allows selection of an appropriate site to insert the needle, which can then be advanced to the node (d). This is a hollow co-axial needle – a trucut core biopsy needle is then inserted through it and the biopsy samples obtained. Lymphoma was confirmed.

CT can also be used for guidance for biopsy of pelvic lesions. This patient previously had a hysterectomy for uterine leiomyosarcoma. Follow-up CT showed a large mass at the right pelvic side-wall (left image, arrows). Biopsy was requested. With the patient prone, a planning CT was performed, again with a grid taped to the patient’s skin (middle image). Appropriate needle length was selected based on the depth of the mass from the skin. Right hand image shows the biopsy needle in the edge of the mass. The biopsy confirmed metastatic leiomyosarcoma.

Bone biopsy

We frequently perform biopsy of lesions identified in the spine, sternum, pelvic bones or the long bones of the extremities. The majority of these require CT guidance for safe access, although some can be accessed using only fluoroscopy for guidance. A hand-held drilling needle is used initially to make a hole in the overlying cortex, following which a hollow needle is used to obtain a sample from the lesion. These are performed as day cases. Complications are rare, but potentially include haemorrhage with spinal cord compression when biopsying vertebral lesions.

Most of the bone biopsies performed at SVUH are for metastases, or occasionally myeloma. We see relatively few primary bone tumours at SVUH, as most of these are dealt with in the paediatric hospitals or in Cappagh Orthopaedic Hospital.

Bone biopsy hand drill (right) and biopsy needle (middle). The trochar on the left is for pushing the bone sample out of the biopsy needle, as it if often firmly stuck in the core of the needle.

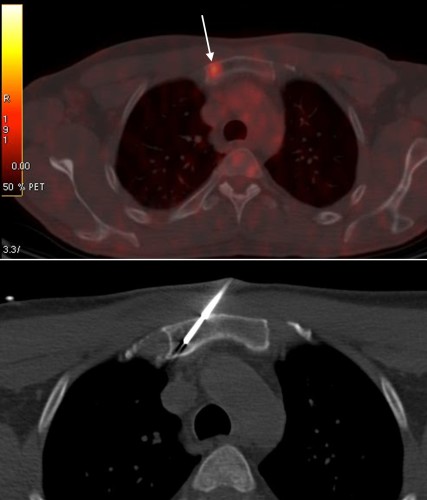

PET/CT performed for staging of lung cancer showed a hypermetabolic focus in the manubrium of the sternum (top image, arrow). CT-guided biopsy of the sternum was performed to confirm metastatic disease, bottom image.

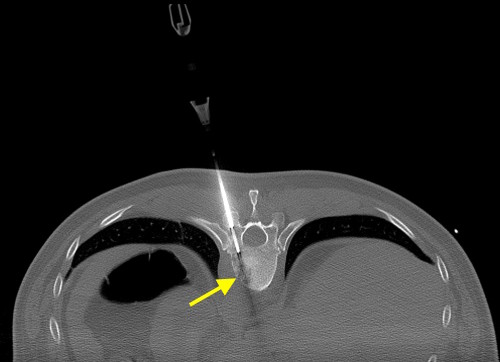

This image is taken from a CT-guided spine biopsy, performed to confirm that the lytic lesion in T10 (arrow) was a metastasis from the patient’s known neck cancer. The biopsy needle has been drilled through the pedicle of the vertebra, just a few millimetres from the spinal cord. Steady hand required!